By Alex Fashandi, Kelsi Morefield, and Michael Gyang

When Cook County paramedic firefighter Tony Lein arrives at the scene of an opioid overdose, he doesn’t see a drug addict or abuser.

Instead, he sees a human being struggling to breathe – a person coping with their troubles and going over the edge.

“The main experiences that I have with people who use opioids is when they overdose on it,” Lein said. “When they take too much and they experience these symptoms of an overdose, they need medical care because it [the opioid] slows everything down. You go unconscious, you’re only breathing a couple times a minute. It slows your heart rate, slows your respiratory drive. So really, they need to have that EMS [Emergency Medical Service] if they want to survive.”

This is a common scene encountered by Lein and similarly by other paramedics on the front lines of the nationwide opioid crisis.

Part of the crisis stems from prescription opioid medications. According to the Washington Post, from 2006 to 2012, enough prescription opioids were prescribed in Chicago’s Cook County to distribute 15 pills per year to each resident – that’s 566,752,649 pills.

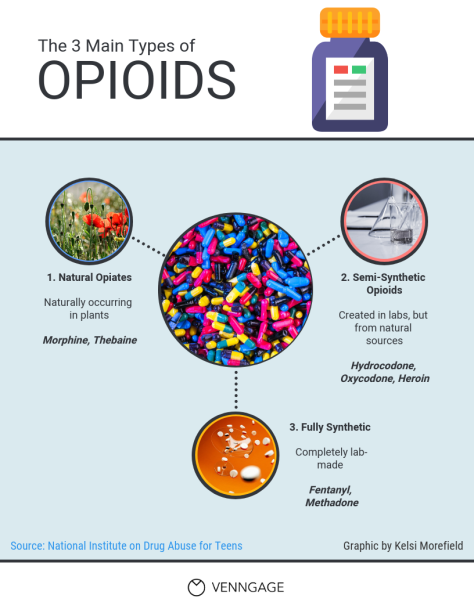

In Cook County, several factors contribute to the opioid epidemic, experts say. Prescription opioids often get the brunt of the blame for it; however, the presence of illicit opioids such as heroin also contribute to the problem in the county. Yet, due to overall increased opioid misuse, the prevalence of stigma has grown towards the use of prescribed opioids as well as the treatment of those with opioid abuse disorders.

In August 2019, the Washington Post released an updated extended database detailing the nationwide opioid crisis in the United States. This data extended to Cook County, and included information on prescription opioid manufacturers, distributors, and distributing pharmacies, as well as overdoses and deaths.

The Post’s database showed that Chicago’s opioid epidemic is more severe than the rest of Illinois. Per capita, Chicago suffered about 12 more deaths in 2017 compared to statewide data. Since 2015, the annual opioid related death rate has increased.

A common misconception about the opioid crisis is that the main culprit is prescription opioid medications, experts say.

Clinical pharmacist Dr. Laura Meyer-Junco posed the question, “if you think opioid prescriptions are solely to blame, then why is it that older adults, those over 55 years of age who are the largest consumers of prescription opioids, have the lowest overdose rate?” Confirming this, data from the Chicago Public Health Department shows that individuals under 55 have a higher occurrence of death and overdose than those over 55.

Meyer-Junco said the country has been looking for a scapegoat within the pharmaceutical industry, and quoted pain patient advocate Dr. Lynn Webster: “‘joblessness homelessness, and despair are greater contributors to the opioid crisis than overprescribing.”

Data supports this theory. According to the American Medical Association, opioid prescriptions have decreased 33% from 2013-2018.

The increase in opioid related deaths combined with the decrease in opioid prescriptions raises the question: Why has the mortality rate risen?

As UIC Director of addiction psychiatry Dr. Christopher Holden said, the problem in Chicago lies with the distribution and use of heroin and other illicit or synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

Confirming what Dr. Holden said, the 2017 opioid surveillance report from the Chicago Department of Public Health shows that heroin use accounted for more opioid-related deaths than fentanyl and opioid pain relievers combined.

For those on the front lines combating the opioid crisis, it doesn’t matter whether the opioid is prescribed or illicit. What matters most is the administering of lifesaving treatment. One common onsight treatment is Naloxone, commonly known by its manufacturer name Narcan. The drug acts as an antagonist, and works to counteract opioid overdoses.

“Narcan is a really incredible medication,” Lein said. “As soon as we start to push it through their veins, it’s almost like an instantaneous thing that they wake up right away… You see somebody at first and they’re almost borderline clinically dead. Then you give this drug and almost immediately they come out of it. It really is an incredible thing to us. It’s one of the most gratifying calls that we can go on, as you see the biggest change in patient condition from the beginning to the end.”

Gratifying as it may be for Lein, there is controversy surrounding the administration of Narcan. For one, it is a drug. The idea of administering a drug to save the life of a drug abuser is one which some are hesitant to accept.

Some experts see Narcan as a tool for enabling abusers. For paramedics, repeat opioid overdose calls are not uncommon. Thus, some healthcare professionals believe that there should be policies in place, such as a three strike rule, so that abusers who have received Narcan more than three times are no longer eligible to receive treatment.

Others say following such policies would go against their ethical code. As Lein said, “It’s almost like underselling the value of human life. Just to say we’re going to give up on you because you made a few mistakes…There’s definitely that mindset, not only in healthcare professionals, but also in normal day to day people that think ‘why give narcan out for free if it’s just enabling the problem?’”

Even in instances in which he encounters an overdose from a previous call, Lein looks on the brighter side. He said, “I still think that there’s hope…it might be the first or second time we administer [narcan], but if we administer it and maybe the right person gets in touch with them, then maybe they’ll turn their lives around.”

Chronic pain treatment is often hindered because of the stigma surrounding it, experts say.

For instance, the CDC released a conservative set of guidelines in 2016 for appropriate opioid prescriptions. Meyer-Junco’s daily work as a patient care physician show those results.

The issue, according to Meyer-Junco, is that chronic pain physicians are being cautioned against giving opioid pain medications because more and more people are starting to equate opioids with addiction.

Holden also mentioned how he sees patients hold stigma towards the medication used to treat their opioid use disorders.

“One of the things I find is that when patients have a heroin use disorder or any sort of opioid use disorder, they’re opposed to medication because of stigma,” he said. “There’s something [they believe is] less noble or less right about trying to be on a medication rather than a straight detox.”

The latter medication Holden referenced were buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone, which are used in opioid medication-assisted treatment. During this treatment, these FDA approved drugs are used in conjunction with counseling and psychosocial support.

There are several groups in the city aiming to combat the opioid crisis. One reliable recovery service is the Chicago Recovery Alliance, recommended by Holden, which has several outreach centers across the city, as well as in surrounding Chicagoland suburbs. They offer services like syringe distribution, addiction treatment referrals, and Narcan to reverse overdoses.

Map of Chicago Recovery Alliance locations around the city of Chicago, both fixed locations and van stops by day of the week.

Yet, as the epidemic gains nationwide coverage, the following question is raised: where should efforts to combat the crisis be directed?

For Meyer-Junco, the solution is multi-faceted. Efforts should go towards ending the trafficking of illicit opioids, as well as to providing resources to communities affected by the problem. To aid these communities, there needs to be better access to opioid treatments, mandated opioid education for prescribers, and better incentives for health professionals to treat those suffering from opioid use disorders.

Lein also stressed education.

However, “with education you have to have people who are willing to listen, want to listen and you have to have some mode of delivering that content to them,” he said.

——-

How to Help

If you or someone you know is struggling with opioid addiction, visit anypositivechange.org to start the road to recovery.